Understanding the Burden of Trust for Business Leaders

According to the Edelman Trust Barometer, businesses have become society’s most trusted institution. What responsibility do they have to put that asset to use to help society solve its problems?

By Nathan Christiansen

Every year since 2000, Edelman, a global public relations firm, has conducted an international survey to assess people’s trust in our core institutions. This survey is called the Edelman Trust Barometer, and earlier this year, Edelman released the most recent results based on responses from more than 36,000 respondents across 28 countries. The results paint a disconcerting but not surprising picture: High levels of distrust that undermine our ability to communicate, collaborate and solve the problems we face.

But within this bleak picture, the Edelman Trust Barometer finds hope in an unexpected place: business. Of the studied institutions, business is the most trusted, with 61% of global respondents reporting that they trust business, compared to 59% for NGOs, 52% for government and 50% for media. Further, business is seen as most capable of solving societal problems and getting results, scoring a startling 53 points higher than the primary institution created to solve societal problems: government.

Businesses are especially trusted by their own employees. Seventy-seven percent of respondents globally, and 74% in the U.S. said they trust their employer. On a more personal level, 66% of respondents said they trust their CEO, and 74% said they trust their coworkers, a trust level second only to scientists.

The burden of trust

Given these results, business leaders need to ask ourselves a question: If our organizations have stores of an increasingly scarce resource — trust — what responsibility do we have to put that asset to use to help society solve our problems?

Our employees and customers have already made up their minds. According to the Edelman Trust Barometer, 58% of people make purchasing decisions, 60% make employment decisions, and 64% make investing decisions based on their beliefs and values. Further, 60% want their CEO to speak out on controversial issues they care about, and 81% want CEOs to be personally visible on public policy issues. As a more specific example, according to the Deloitte Global 2022 Gen Z and millennial survey almost half of Gen Zs (48%) and millennials (43%) say they have put some pressure on their employer to take action on climate change, for example.

This is likely unsurprising but unwelcome news to CEOs. Historically, many business leaders have avoided wading into the murky waters of societal matters. Unless the issue had clear implications for the bottom line, it was considered distracting at best and dangerous at worst to get involved.

A world in which every business engages on every issue society deems important would be noisy, disorienting and unproductive. But the trust people have placed in businesses, and specifically their own employers, creates an opportunity, responsibility and pathway for business leaders to act. The challenge is deciding when to do so, especially given the pace of change, the divisiveness in society, as well as the limitations of time, attention and resources.

When should business leaders act on these issues?

The key for businesses is to speak and act when they have a credible reason to do so. Without a credible reason, corporate action becomes performative, confusing, or even counter-productive, and often erodes trust. But with a credible reason to act, corporate action has a much higher likelihood of achieving the three “i”s: intentional, informed and impactful. Businesses can determine whether they have a credible reason to speak or act on an issue by examining the issue along three dimensions:

- Impact to mission: A company’s purpose for existing is defined by its mission and how it will achieve that mission is defined by its values. Therefore, the first step is to assess the extent to which an external event or issue impacts the ability of an organization to fulfill its mission and values. For example, at Mineral, our mission is to help businesses and their people thrive at work. So, we look first at whether an issue obstructs, enhances or doesn’t affect employers’ ability to create a thriving team. Issues like anti-harassment, pay equity or mental health are highly relevant to what we consider ingredients to a thriving team, while an issue like animal cruelty is less relevant.

- Employee impact: The second dimension to examine is the extent to which an external event or issue affects a business’s employees. This requires looking beyond employees’ work experience to their overall life experience, including their families and communities. At Mineral, we’ve identified events and issues such as natural disasters, civil rights legislation, climate change and racially-motivated hate crimes as ones that materially affect the well-being of our employees and their families.

- Customer impact: The third dimension to examine is the extent to which an issue or event affects customers. Similar to the employee view, this view requires looking at the health and well-being of customers beyond a business’s commercial relationship with them. For instance, at Mineral, our customers are U.S.-based small and mid-size businesses. When the Covid pandemic caused the closure of businesses nationwide in the spring of 2020, we joined campaigns to financially support these businesses until the economy could be reopened.

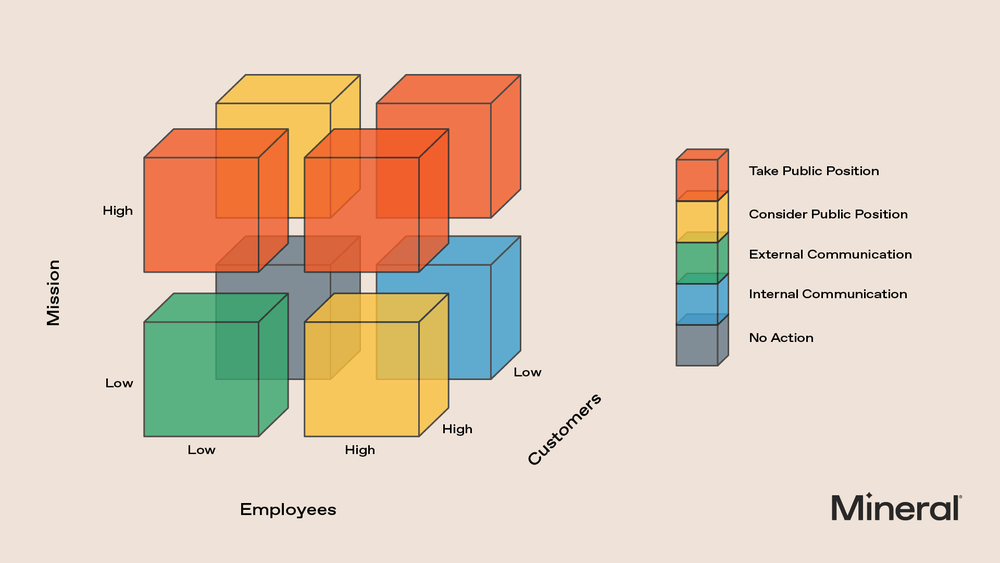

Decision matrix

The more significant the impact on these dimensions, the more credible the reason for a business to act. Here is a simple decision matrix for deciding when and how to act based on these considerations:

Let’s start with the red zones. If an issue or event has a high impact on a company’s mission and its employees or customers, a company has a highly credible reason to act. And if it does so, its action is likely to reflect the three “i’s” above: intentional, informed and impactful. Corporate action could include using a website, social media, or thought leadership to promote a position or taking direct action through volunteerism or financial contributions.

Now to the orange zones. If an issue has a high impact on a company’s mission, but a low impact on its customers and employees, then the company should do further analysis to determine whether action or a public position is appropriate. The same would be true if an issue has a high impact on customers and employees, but a low impact on the mission. Further analysis may include evaluating whether the company has a unique perspective to offer or whether it can take meaningful action to get results.

Now to the green and blue zones. If an issue or event has a high impact on customers, but a low impact on the mission and employees, a company can use external customer communication to respond to the issue. For instance, external communication may mean sending an email to customers acknowledging the issue and the company’s stance on or response to it. Similarly, if an issue or event has a high impact on employees, but a low impact on the mission and customers, the company can use internal employee communication to respond to the issue.

Last is the gray zone. If an issue or event has a low impact on the mission, employees and customers, the company likely does not have a credible reason to act. This does not mean the issue or event is not important to society. It simply means the company’s involvement may not be productive, or at least sufficiently productive, to justify taking time, attention and resources away from other efforts. The company’s executives and employees could certainly still engage on the issue as individuals in their personal capacity.

As indicated in the Edelman Trust Barometer, businesses now have a powerful and unique combination of advantages — trust and competence — but they must use them wisely. Business leaders need to embrace the role their employees and customers have bestowed upon them, focusing on issues where there is a credible reason to act and finding that credibility through the impact on the business’s mission, employees and customers. By taking these steps, businesses can step confidently from the conference room to the town square, driving positive change both for their own companies and on an even broader level.